[This is another very old story, with photos from trips to Cape Hatteras National Seashore in 1978, 1980 and 1981.]

Cape Hatteras lies in the Outer Banks, a 200-mile-long string of barrier islands that form most of the North Carolina coastline. It’s an area of subtle beauty where sea oats sit atop the dunes and provide a backdrop to long stretches of soft sand beaches that offer a playground to tourists.

Cape Hatteras is located in Cape Hatteras National Seashore, which was established by Congress on August 11, 1937, as part of the National Park System. It extends along the North Carolina coast for about 70 miles and includes Bodie, Hatteras and Ocracoke Islands. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean on the east and Pamlico Sound on the west. Although eight small villages sit on the Pamlico Sound side of Hatteras Island, the entire 70-mile ocean-side of the National Seashore is open to the public.

The Outer Banks are an important area oceanographically, for this is where the Gulf Stream, bringing warm water up from the South, meets the Labrador Current, bringing cold water down from the North. The convergence of these two currents creates a treacherous region of storms, strong tides, and rapidly shifting shoals that has lead to so many shipwrecks that it has often been called the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

To assist navigation through this hazardous stretch of water, Congress authorized the construction of lighthouses on the Outer Banks. The Bodie Island Lighthouse is north of Oregon Inlet at the north end of the seashore. The first Bodie Island Lighthouse was abandoned due to a poor foundation. The second one was destroyed by retreating Confederate soldiers during the Civil War. The third, which stands today, was built in 1872 and stands 170-feet tall.

The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, like the Bodie Island light, has also had several incarnations. The first, built in 1802, was 95 feet tall. It was extended to 150 feet in 1851. The current lighthouse was constructed in 1870. Its 210-foot height makes it the tallest brick lighthouse structure in the United States and 2nd in the world. Due to erosion of the shoreline, the encroaching ocean seriously threatened the structure. In 1999, with the shoreline only 15 feet away, the lighthouse was moved 2900 feet to it’s current location.

As can be seen in the photo above, the Bodie Island and Cape Hatteras lights are each painted with distinctive markings to assist with navigation during the daytime. These are referred to as “daymarks.” The lighthouses emit distinctive light sequences at night to aid with identification and location in the dark.

This was before the lighthouse was moved in 1999.

The Ocracoke Lighthouse is located in Ocracoke, a town on the southern tip of Ocracoke Island. It stands 75 feet tall and was built in 1823 to help guide ships through Ocracoke Inlet into Pamlico Sound. It’s the oldest operating light station in North Carolina.

In addition to lighthouses, the government eventually established life saving stations. According to the National Park Service, “[m]ore consideration was given to the cargo lost in shipwrecks than to the human victims of such disasters.” But, in 1848, money was finally budgeted for life-saving services. Not very effective at first, in 1878, the U.S. Lifesaving Service was made an independent unit of the Treasury Department.

The Chicamacomico Lifesaving Station was one of seven North Carolina lifesaving stations commissioned by the federal government. Congress appropriated $200,000 towards the building and staffing of these stations, an action that was spawned by increasing reports of regular deadly shipwrecks that were occurring off the coast, thanks mainly to the Diamond Shoals.

Although we camped at several of the four campgrounds in the seashore, most of the time we stayed in the Ocracoke campground, which was about five miles north of the town of Ocracoke. It was rather rustic in 1980. There were no bathrooms, just molded-plastic portable toilets scattered around the campground. Water was available from faucet-topped pipes and showers consisted of four-foot square plywood floors with slightly raised five-foot high plywood walls. The heads and feet of taller users could be seen but shorter users only showed their feet. An interesting feature of the water was that it was too warm for drinking but too cold for showering.

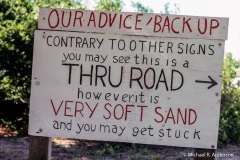

When we needed supplies or were just tired of cooking meals over the Coleman stove, we could drive down to Ocracoke and get whatever we wanted. We discovered that an important supply we needed right away was long tent stakes. They are definitely required when camping on sand unless you don’t mind having your tent relocated by strong ocean breezes.

If you haven’t seen enough, the slide show below has 15 more photos from Cape Hatteras. Click on an image to enlarge it and use arrow keys to advance.

And, of course, when your kids are young, you love to take pictures of them and they love to pose. This is one of my favorites.

Finally, if Cape Hatteras is not enough seashore for you, you can continue south to Cape Lookout National Seashore, which extends down the North Carolina coast for another 56 miles.